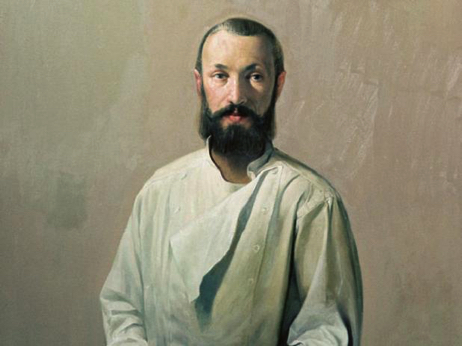

Bakhtin’s concept of the carnival and the carnivalesque novel.

Julia Kapuśniak

The principle of laughter and the carnival spirit on which the grotesque is based destroys this limited seriousness and all pretense of an extratemporal meaning and unconditional value of necessity. It frees human consciousness, thought, and imagination for new potentialities. For this reason, great changes, even in the field of science, are always preceded by a certain carnival consciousness that prepares the way.

― Mikhail Bakhtin

The carnival is a celebration of life taking place in many countries all over the world once a year. As The Columbia Encyclopaedia explains, the carnival is a celebration of all people, despite their status and position in social hierarchy, which takes place just before Lent. Lent derived from Old English ‘lencten’ means spring.

Since early times carnivals have been accompanied by parades, masquerades, pageants, and other forms of revelry that had their origins in pre-Christian pagan rites, particularly fertility rites that were connected with the coming of spring and the rebirth of vegetation.

Before discussing Bakhtin’s concept of the carnival and carnivalesque novel it seems useful to introduce a brief analysis related to the origins of the culture of folk humour and carnival itself visible through the epochs.

One characteristic feature of the carnival was creating separate laws which applied only during its period of subversive potential which changed established order. Additionally, the carnival created a new kind of relations between its participants which were in opposition to social relations in the time outside of the carnival.

According to Bakhtin, the significance of the culture of folk and humour was tremendous in the Middle Ages. There was a wide range of humorous forms such as traditional folk ceremonies (of carnival type), comic rituals, jugglers, clowns and dwarfs. All of these forms are linked with the culture of folk carnival humour. These forms may be divided into three general groups. The first group are ritual spectacles which include carnival pageants and comic shows of the market place. The second group is comic verbal compositions which include oral and written parodies. The last group are various genres of billingsgate: curses, formal promises and blazons. It is important not to link the carnival rituals with religion and “ecclesiastic dogmatism.”

For Mikhail Bakhtin, carnival has a liberating potential, as during its time the church and state has no control over the lives of people. The liberating potential of the carnival can be seen in the fact that set rules and beliefs were not protected from ridicule or reconception at carnival time; it “cleared the ground” for new ideas to enter into public speech. Bakhtin sees carnival as an occasion in which the political, legal and ideological authority of both the church and state were inverted during the anarchic and liberating period of the carnival:

All these forms of protocol and ritual based on laughter and consecrated by tradition existed in all the countries of medieval Europe: they were sharply distinct from the serious official, ecclesiastical, feudal, and political cult forms and ceremonials. They offered a completely different, nonofficial, extra ecclesiastical and extra political aspect of the world, of man, and of human relations; they built a second world and a second life outside officialdom, a world in which all medieval people participated more or less, in which they lived during a given time of the year. If we fail to take into consideration this two-world condition, neither medieval cultural consciousness nor the culture of the Renaissance can be understood. To ignore or to underestimate the laughing people of the Middle Ages also distorts the picture of European culture's historic development. (Rabelais and His World 5-6)

The culture of laughter is not an artistic form but is placed somewhere between art and real life. People are not just actors , they live in this world and everyone participates because the idea of carnival includes all the society:

Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people. While carnival lasts, there is no other life outside it. During carnival time life is subject only to its laws, that is, the laws of its own freedom. It has a universal spirit; it is a special condition of the entire world, of the world's revival and renewal, in which all take part.

During the period of carnival life stands only for its own laws and its own freedom. As an example we can recall Roman Saturnalia. Saturnalia was the most popular holiday of the Roman year. Seneca describing Saturnalia said “whole mob has let itself go in pleasures.” (“Moral letters to Lucilius,” Letter 18). Saturn’s festival, Saturnalia, became the most popular of Roman festivals. Saturnalia was originally celebrated on December 17, but later was celebrated for seven days. During Saturnalia all work and business were suspended. Moreover, slaves were given temporary freedom. For this particular period of time they could do and say what they wanted. Coming back to Bakhtin, he claims that the Roman tradition of Saturnalia continued to exist in the medieval carnival: the tradition of the Saturnalias remained unbroken and alive in the medieval carnival, which expressed this universal renewal and was vividly felt as an escape from the usual official way of life .

While talking about the culture of carnival and humour it is essential to mention one very important figure, which is characteristic for the medieval culture of humour, i.e. a carnival fool. Carnival clowns and fools were inseparable and typical models of the carnival spirit outside the carnival season. It is necessary to point out that clowns and fools at that time were present at the courts all around Europe. The medieval fool was not only the source of enjoyment, but also degraded gestures of high ceremonials and rituals to the material sphere. Moreover, clowns and fools were not actors during the time of feast but remained fools and clowns wherever they were appearing:

Clowns and fools [..] are characteristic of the medieval culture of humour. They were the constant, accredited representatives of the carnival spirit in everyday life out of carnival season. Like Triboulets at the time of Francis I, they were not actors playing their parts on a stage, as did the comic actors of a later period, impersonating Harlequin, Hanswurst, etc., but remained fools and clowns always and wherever they made their appearance. As such they represented a certain form of life, which was real and ideal at the same time.

Both official and unofficial feasts were equally important forms of human culture. The feasts of the Church differed from the unofficial ones. During the feasts led by the Church there was no place for liberation of people and for creating a second life, as it happened during the unofficial feasts. The link with the time became formal. The official feasts clearly depicted the existing hierarchy of moral, political and religious values. The triumph of truth was eternal and indisputable. There was no space for laughter.

The official feasts of the Middle Ages, whether ecclesiastic, feudal, or sponsored by the state, did not lead the people out of the existing social order and offered no alternative forms of life. On the contrary, they sanctioned the existing pattern of things and reinforced it. The link with time became formal; changes and moments of crisis were relegated to the past. Actually, the official feasts looked back to the past and used the past to consecrate the present:

Unlike the earlier and purer feast, the official feast asserted all that was stable, unchanging, perennial: the existing hierarchy, the existing religious, political, and moral values, norms, and prohibitions. It was the triumph of a truth already established, the predominant truth that was put forward as eternal and indisputable. This is why the tone of the official feast was monolithically serious and why the element of laughter was alien to it. The true nature of human festivity was betrayed and distorted. But this true festive character was indestructible; it had to be tolerated and even legalized outside the official sphere and had to be turned over to the popular sphere of the marketplace.

Opposing the official feasts , the unofficial feasts were celebrated in disconnection from the truth and social order. At that time all hierarchical order and norms were held in abeyance. The carnival meant the true feast of time, becoming, change and renewal. While

the order and rank were the most noticeable during the official feasts (the clergy and officials were expected to wear the official attire corresponding to their rank), during the carnival everyone became equal despite of their position in the society, status and occupation. The social divisions between people which had existed for ages did not matter during the carnival.

“People were, so to speak, reborn for new, purely human relations” – during the carnival people became “a part of utopian ideal” which was a peculiar experience. This event led to a special form of communication which was only present at the time of the carnival “ the speech of marketplace”. This type of communication was free from social norms and etiquette. It made it possible to erase social divisions which otherwise prevented different classes from interacting from one another.

Another aspect worth mentioning is carnival symbols. They appeared in the ancient rituals, starting with Roman Saturnalia were also present in Medieval carnival celebrations. These symbols represented change and renewal and a logic which Bakhtin calls “inside out logic” derived from French a l’enves. Some of typical carnivalesque types of images are images of the human body with food, drink, defecation and sexual life. Later on these symbols used in art and literature were associated with specific movements, such as “naturalism” or “biologism”. In the Renaissance they were interpreted as a “rehabilitation of the flesh”.

Carnivalization for Bakhtin is something more profound than traditional liturgical celebration of the time before Len. Carnivalization is related to an outlook opposing official institutions and hierarchical order, which suggests the carnival’s subversive potential. Furthermore, the carnival leads to suspension of law ,order and official hierarchies.

In general, carnivalesque literature is closely connected with the usage of all kinds of carnival forms ,images and carnivalesque creations. Thanks to celebration of carnival forms and the carnival itself, it is said to be “recreational literature”(72) of the Middle Ages. Carnivalesque literature takes its origins from Christian and ancient past and includes many literary genres and styles which shares carnivalesque spirit and symbols. During the period when comic literature was written in Latin, a parody and semi parody became popular. One of the most recognizable example was “Coena Cypriani” – an anonymous prose work written in the early Middle Ages. Other examples include parodical liturgies, parodies of Gospel readings and prayers such as Ave Maria, hymns, psalms and litanies.

The comic literature of the Middle Ages developed throughout a thousand years or even more, since its origin goes back to Christian antiquity. During this long life it underwent, of course, considerable transformation, the Latin compositions being altered least. A variety of genres and styles were elaborated. But in spite of all these variations this literature remained more or less the expression of the popular carnival spirit, using the latter's forms and symbols. The Latin parody or semi parody was widespread. The number of manuscripts belonging to this category is immense. The entire official ideology and ritual are here shown in their comic aspect.

Carnivalesque communication may be presented on the example of two persons who at the beginning of the relation are not familiar with each other, which may also mean that they cannot express themselves in a free, relaxed way. Their form of speech seems more strict and formal. With the passing of time, when they get more familiar with each other, (they become friends), the style of their communication changes and becomes more relaxed: the verbal etiquette becomes less strict and less formal expressions occur. Mutual mockery is permitted, they may address each other informally and use abusive words. We can also identify typical carnivalesque gestures, such as patting each other’s shoulders or even patting each other’s bellies. The speech patterns typical of carnivalization are abusive language, insulting and mocking words or expressions(the abuse is grammatically and semantically isolated from the context).

Bakhtin’s carnival is a “manifestation of folk laughter” and influences not only the lives of its participants but also literature. These festive forms of Middle Ages and Renaissance mentioned by Bakhtin in his work find their representation in literary works- as an example of carnivalesque literature Bakhtin gives Boccaccio’s Decameron. Bakhtin writes that in carnivalesque literature, the comic and tragic aspects coexist together and become one aspect “In world literature […]seriousness and laughter, coexist and reflect each other, and are indeed whole aspects, not separate serious and comic images”(122). The subversive potential of the carnival time favours a different approach to life and, is related to various forms of behaviour which would have never been accepted at a non-carnival time. Moreover, Bakhtin talks about the act of decrowning of the king and crowning of the carnival king which shows the subversiveness of carnival acts which mock the reality and oppose the authorities and social hierarchies.

Although Muriel Spark’s novel The Ballad of Peckham Rye is not a strictly carnivalesque text as understood in Bakhtin’s theory, it does include some typical features of the carnival and it seems to be written in a “carnivalesque spirit.”